|

Santa Cruz Island Crossing the Santa Barbara Channel on a Mystere 6.0 By Bill Mattson |

|

On the weekend of July 20th, a friend and I successfully crossed the Santa Barbara Channel and

landed on aboard a

6.0 beach catamaran. The trip

included an 11 hour sailing leg, some rough conditions, and an overnight stay on the island.

Although the trip was cut short by some crippling boat damage, it still was one of the most

exciting adventures I have had in a long time.

The trip started as an idea I had back in 1997. At the time, the plan was for four people to cross the channel on two Hobie 16s. Research on conditions in the area left me unsure as to the whether the Hobie 16 was a large enough boat for such an undertaking. Two years later, my entry in the Milt Ingram Race reinforced my doubts, as I was not able to successfully complete the race on my Hobie 16 after having run into very rough seas and high winds. Since then, the Milt Ingram race committee has a strict size limit, in that no boats under 18 ft. may enter the race. Earlier this year, Gary Friesen and I began discussing making the crossing aboard his Mystere 6.0. Our discussions, mainly done via email, revealed that both of us were quite excited over the prospect of making such a trip. More importantly, we both had a keen awareness of its hazards and the safety measures that would be required to pull it off. This was no casual undertaking.  Santa Cruz Island is part of the Channel Islands National Park, which is located off the coast of

Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties, in Southern California. The largest of the Islands, Santa

Cruz is over 96 square miles in size and approximately 22 miles long. Its northern side ranges

from 19 to 25 miles from the California coast. The islands central valley is located between two

mountain ranges, which reach to over 2,000 ft. While much of the Islands coastline is rugged

cliffs, there are numerous small beaches and anchorages located in coves all over the Island.

The history of the Island ranges from indian inhabitants of 10,000 years ago, to private ranching

operations, to the present ownership of the National Park Service and Land Conservancy. Much Santa Cruz Island is part of the Channel Islands National Park, which is located off the coast of

Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties, in Southern California. The largest of the Islands, Santa

Cruz is over 96 square miles in size and approximately 22 miles long. Its northern side ranges

from 19 to 25 miles from the California coast. The islands central valley is located between two

mountain ranges, which reach to over 2,000 ft. While much of the Islands coastline is rugged

cliffs, there are numerous small beaches and anchorages located in coves all over the Island.

The history of the Island ranges from indian inhabitants of 10,000 years ago, to private ranching

operations, to the present ownership of the National Park Service and Land Conservancy. Much

of this rich history is covered in the books by John Gherini, and by Margaret Holden Eaton. Currently The Nature

Conservancy owns the majority of the island, with a smaller section belonging to the National

Park Service. The division is at the west side of the Islands isthmus, on a line, which runs from

Prisoners Harbor to Valley Anchorage. The Park Service property is east of this line. of this rich history is covered in the books by John Gherini, and by Margaret Holden Eaton. Currently The Nature

Conservancy owns the majority of the island, with a smaller section belonging to the National

Park Service. The division is at the west side of the Islands isthmus, on a line, which runs from

Prisoners Harbor to Valley Anchorage. The Park Service property is east of this line.

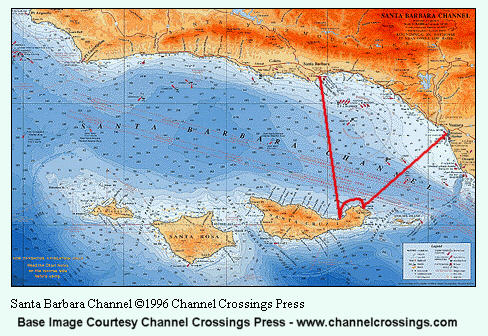

The Scouting Trip  The first of our trips took place on June 23, 2001. In the weeks prior, we carefully researched wind and weather patterns. Two very useful resources are  maintained by the US Navy, and from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The first

crossing would be a one-day trip to determine good landing sites for a two or three-day trip in the

future. While a much shorter crossing is available from Ventura (approx. 19 mi.), wind patterns

as well as conversations with seasoned area sailors suggested that we take a longer trip from

Santa Barbara. This would provide a broad reach all the way to our first stop: Chinese Harbor.

From here, we would round Cavern Point to Scorpion Anchorage. If time permitted, we would sail

to Smugglers Cove, then would head home to Ventura. maintained by the US Navy, and from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The first

crossing would be a one-day trip to determine good landing sites for a two or three-day trip in the

future. While a much shorter crossing is available from Ventura (approx. 19 mi.), wind patterns

as well as conversations with seasoned area sailors suggested that we take a longer trip from

Santa Barbara. This would provide a broad reach all the way to our first stop: Chinese Harbor.

From here, we would round Cavern Point to Scorpion Anchorage. If time permitted, we would sail

to Smugglers Cove, then would head home to Ventura.

Since we were departing from Santa Barbara, and returning to Ventura, a car was spotted at Ventura the morning of our trip. We met at Ventura at 6:00am, left a car, then drove to Santa Barbara to launch the boat. Garys boat was equipped with a furling jib, furling chuter, and a custom made forward cargo trampoline. Although we only planned for a one-day trip, we were equipped with food, water, a tent, sleeping bags, and clothing to accommodate an overnight stay should conditions turn bad that night. (Actually,  while Gary had a tent, he mistakenly did not pack the tent poles, nor a sleeping bag. He had alternatives such

as a sail bag and sails, but did not sound overly anxious to use them.) Gary

had obtained a campsite reservation from the National Park Service. I had obtained a landing

permit from the Nature Conservancy. While we could camp at Scorpion Anchorage, we could only

spend daylight hours on Land Conservancy property, providing a valid permit is held. Access to

the central valley is not permitted at any time. while Gary had a tent, he mistakenly did not pack the tent poles, nor a sleeping bag. He had alternatives such

as a sail bag and sails, but did not sound overly anxious to use them.) Gary

had obtained a campsite reservation from the National Park Service. I had obtained a landing

permit from the Nature Conservancy. While we could camp at Scorpion Anchorage, we could only

spend daylight hours on Land Conservancy property, providing a valid permit is held. Access to

the central valley is not permitted at any time.

The Santa Barbara Channel is known for quick changing conditions. Winds in the range of 30 knots are common near the Island, with winds to 50 kts possible throughout the year. Other hazards include steep swell conditions, cold water, fog, and freighter traffic. In the case of a capsize, the hazards then include sharks and cold water. Gary and I share a good appreciation of these hazards, and had agreed that any decision to proceed would have to be a unanimous one. Either person had the option of calling off the trip turning back at any time.  All camping gear and clothing were contained in Texsport water-proof float bags strapped to a

cargo trampoline just forward of the main beam. Electronic gear included a VHF radio, a

cellphone, and two GPS units preloaded with trip waypoints. Safety gear included handheld and

aerial flares, whistles, flashlights, marker dye, signal mirrors, signal smoke, and two paddles, and

a Solo~Right. All camping gear and clothing were contained in Texsport water-proof float bags strapped to a

cargo trampoline just forward of the main beam. Electronic gear included a VHF radio, a

cellphone, and two GPS units preloaded with trip waypoints. Safety gear included handheld and

aerial flares, whistles, flashlights, marker dye, signal mirrors, signal smoke, and two paddles, and

a Solo~Right.

This first trip was largely uneventful. Light to moderate winds were experienced on the way to the

island, with winds near zero at midday. Visibility appeared to be about 2 miles in the low marine

layer. The boat traffic we expected on a weekend was simply not there. It was somewhat spooky

to be drifting around in light winds and calm water with no land references anywhere in sight. Soon

the winds gradually picked up, and we were on our way again. After about 3 hours into the trip,

we started to make out a land mass in the distance. Santa Cruz Island. The GPS units had not let

us down. The winds picked up to a moderate 10-12 knots near the island, and we soon reached

This first trip was largely uneventful. Light to moderate winds were experienced on the way to the

island, with winds near zero at midday. Visibility appeared to be about 2 miles in the low marine

layer. The boat traffic we expected on a weekend was simply not there. It was somewhat spooky

to be drifting around in light winds and calm water with no land references anywhere in sight. Soon

the winds gradually picked up, and we were on our way again. After about 3 hours into the trip,

we started to make out a land mass in the distance. Santa Cruz Island. The GPS units had not let

us down. The winds picked up to a moderate 10-12 knots near the island, and we soon reached

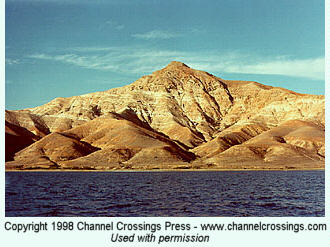

the rugged shoreline, in a total trip time across the channel of four and ½ hours. The shoreline of

Santa Cruz is a spectacular site. Waves crashing into rugged cliffs toped with a scenic vista of

mountains, trees and prairies. Not until you approach it do you realize just how enormous it is.

The scenery, coupled with the catamaran sailing is a unique experience that could never be

captured on film. Sailing the coast of Santa Cruz has put images in my head that will always be

remembered. the rugged shoreline, in a total trip time across the channel of four and ½ hours. The shoreline of

Santa Cruz is a spectacular site. Waves crashing into rugged cliffs toped with a scenic vista of

mountains, trees and prairies. Not until you approach it do you realize just how enormous it is.

The scenery, coupled with the catamaran sailing is a unique experience that could never be

captured on film. Sailing the coast of Santa Cruz has put images in my head that will always be

remembered.

At Chinese Harbor, we found a sheltered cove with very little wind. After paddling for

a few minutes, it became clear that we would not be able to reach the beach and have enough

time to visit our primary objective: Scorpion Anchorage. So we abandoned the attempt to land at

Chinese, and sailed another two hours to Scorpion. At Chinese Harbor, we found a sheltered cove with very little wind. After paddling for

a few minutes, it became clear that we would not be able to reach the beach and have enough

time to visit our primary objective: Scorpion Anchorage. So we abandoned the attempt to land at

Chinese, and sailed another two hours to Scorpion.

Upon reaching Scorpion Anchorage, we found a few boats moored as well as kayaks on shore.

While the landing was on a sandy beach, there were quite a few rocks scraping the hulls as we

hit shore. (Ouch!).After landing the boat, we had help from some other visitors in getting it above

the tideline. We then took a short walk to the campground, and met the ranger who lives on the

island. He gave us extensive information on places to sail and hike to. Of particular interest was

Painted Cave, a sea cave with a 120 ft high and 100 ft wide entrance. Upon reaching Scorpion Anchorage, we found a few boats moored as well as kayaks on shore.

While the landing was on a sandy beach, there were quite a few rocks scraping the hulls as we

hit shore. (Ouch!).After landing the boat, we had help from some other visitors in getting it above

the tideline. We then took a short walk to the campground, and met the ranger who lives on the

island. He gave us extensive information on places to sail and hike to. Of particular interest was

Painted Cave, a sea cave with a 120 ft high and 100 ft wide entrance.

"You could sail your boat

right into it", he said. This would be a definite goal for our next trip. We determined that Scorpion

would provide an adequate landing and camping spot for the future trip, took a few pictures, then

got back to the boat and left for Smugglers cove. "You could sail your boat

right into it", he said. This would be a definite goal for our next trip. We determined that Scorpion

would provide an adequate landing and camping spot for the future trip, took a few pictures, then

got back to the boat and left for Smugglers cove.

While winds in the Channel had increased, winds on the east side of the island were very fluky

and reversing in different directions. It was now 5:30pm, and it was decision time. Smugglers

Cove was at least an hour in the opposite direction of our trip home. Clearly, we did not have

enough time to make it. After discussing our options, we decided to head for home. While winds in the Channel had increased, winds on the east side of the island were very fluky

and reversing in different directions. It was now 5:30pm, and it was decision time. Smugglers

Cove was at least an hour in the opposite direction of our trip home. Clearly, we did not have

enough time to make it. After discussing our options, we decided to head for home.

The winds on the way home were a respectable 15 kts, and the trip would be a broad reach all

the way there. It would be a 2 hour crossing home, double trapped the entire way. We concluded

our trip pulling up to the dock in Ventura Harbor in the setting sunlight at 7:30pm. The winds on the way home were a respectable 15 kts, and the trip would be a broad reach all

the way there. It would be a 2 hour crossing home, double trapped the entire way. We concluded

our trip pulling up to the dock in Ventura Harbor in the setting sunlight at 7:30pm.

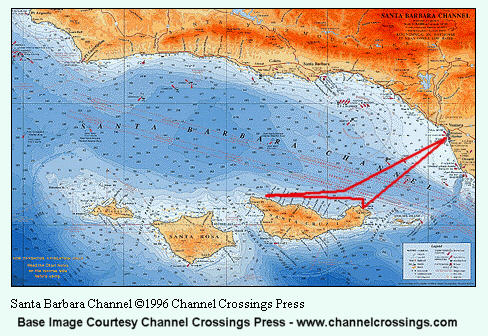

The Second Crossing  Our second crossing and camping trip to Santa Cruz took place on Friday, July 20, 2001. While we had stated our intentions on the Internet, and hoped another one or two boats would be with us, nobody else decided to make this trip. After continued monitoring of the wind and ocean conditions during the previous weeks, we determined that leaving from Ventura would be doable, especially since we were spending the night and did not need time to return the following day. This plan would avoid the complicated logistics of getting cars in place for separating launching/landing areas. In addition to our original list of items, Gary had obtained a small 12 pound outboard motor, and had fabricated a carbon-fiber motor mount for the rear of the boat. The motor would be stowed on the rear of the trampoline, and would accommodate cruising in sheltered coves of the island, as well as provide a backup in the event of low wind or catastrophic rig failure. We now had three waterproof expedition bags holding camping gear, food, and clothing for 3 days. The plan for the weekend was to navigate the channel from Ventura Harbor to the east side of Santa Cruz Island, (near Scorpion Anchorage) a distance of approximately 19 mi. We would then "beat" against wind and swells to the west side of the Island to "Painted Cave. If conditions permitted, we would lower the sails, mount the outboard, and motor into the cave. We would then turn around and attempt landing at Fry's Harbor and Chinese harbor, then land again at Scorpion Anchorage at the far east end of the Island. We would camp at Scorpion for the night, then hike the Island on Saturday before returning on Saturday afternoon. Again, due to the unpredictable nature of weather/sea conditions in the area, we were provisioned to stay an extra day, should conditions be deemed too rough on Saturday afternoon. We departed Ventura Harbor at 9:30am on Friday in light to moderate conditions. Winds during the crossing were in the 12-15 knot range. Numerous dolphins were seen during the trip, with one surfacing between the bows at one point. After 3 1/2 hours, we arrived at a point off the coast of Coche Point, at the east side of the island. We had made significantly better time than we had expected, given our discussions with those who have made this crossing before. We then made our first tack of the day, and began beating against wind and seas that were gradually increasing. Within 2 hours, things started getting exciting. The wind had increased to 25 knots  sustained,

with gusts to over 29 knots, according to saved data from NOAA Santa

Barbara Weather Buoy).

Swells were 3 feet, with 5 foot wind waves. Significant wave heights were

reported at 8 feet, and wave/swell conditions were categorized as "very

steep". The chuter was furled (stored), and the jib/main were depowered as

much as possible. At one point, the luff zipper on the jib failed, forcing

us to furl it as it began flapping off of the forestay. Under close hauled

depowered main alone, our speed upwind was good enough to get the boat completely

airborne over the larger, steeper sets of waves. Both of us were trapped out, and maintaining

footing was a

challenge. At one point I needed to return to the trampoline to secure a

cargo bag. While fighting with the tiedowns in the spray, I felt myself go

weightless as the boat came over a wave, then was slammed into the

trampoline when the boat came down. It was far safer (and dryer) on the

trapeze. sustained,

with gusts to over 29 knots, according to saved data from NOAA Santa

Barbara Weather Buoy).

Swells were 3 feet, with 5 foot wind waves. Significant wave heights were

reported at 8 feet, and wave/swell conditions were categorized as "very

steep". The chuter was furled (stored), and the jib/main were depowered as

much as possible. At one point, the luff zipper on the jib failed, forcing

us to furl it as it began flapping off of the forestay. Under close hauled

depowered main alone, our speed upwind was good enough to get the boat completely

airborne over the larger, steeper sets of waves. Both of us were trapped out, and maintaining

footing was a

challenge. At one point I needed to return to the trampoline to secure a

cargo bag. While fighting with the tiedowns in the spray, I felt myself go

weightless as the boat came over a wave, then was slammed into the

trampoline when the boat came down. It was far safer (and dryer) on the

trapeze.

I must say, these conditions were about the roughest I had been in for the size boat we were on. Soon we were on a layline to Painted Cave, according to the GPS. After reaching the point on the island marked by the GPS, I was sure we had found the cave, but upon closer inspection it was found to be too small.  Assuming an inaccurate GPS entry, we continued tacking

up the Islands coast. While we saw land features which resembled the cave at a distance, closer

inspection revealed them to be some other land feature. With the rough conditions, we could not

get very close anyway. A capsize near the waves that crashed into the rugged cliffs would spell

disaster. After 5 hours of beating through these rough conditions, we abandoned the search at

6:30pm and headed back to Scorpion while we still had daylight. With a new moon, there would

be no light to work with once the day was over. Later, a discussion with kayakers regarding

Painted Cave revealed that it is located within a canyon and not easily seen from the open ocean. Assuming an inaccurate GPS entry, we continued tacking

up the Islands coast. While we saw land features which resembled the cave at a distance, closer

inspection revealed them to be some other land feature. With the rough conditions, we could not

get very close anyway. A capsize near the waves that crashed into the rugged cliffs would spell

disaster. After 5 hours of beating through these rough conditions, we abandoned the search at

6:30pm and headed back to Scorpion while we still had daylight. With a new moon, there would

be no light to work with once the day was over. Later, a discussion with kayakers regarding

Painted Cave revealed that it is located within a canyon and not easily seen from the open ocean.

During the trip downwind, the sun began to set, and it looked like we were going to cut it close as

far as landing while we still had light. In my wetsuit spray top combination, I was getting cold, and

was anxious about getting in before sundown. Gary expressed concern about my condition, since

once the sun went down, the temperature would fall rapidly. He suggested I eat something to get

my metabolism going, so I had some trail mix. In the following swells, it was a wet ride. While

Garys motor mount had been completely out of the way so far, it was now hitting the water

between swells. The water would hit the mount, then shoot straight up just before showering the

skipper. Back to the drawing board on that one, I guess. During the trip downwind, the sun began to set, and it looked like we were going to cut it close as

far as landing while we still had light. In my wetsuit spray top combination, I was getting cold, and

was anxious about getting in before sundown. Gary expressed concern about my condition, since

once the sun went down, the temperature would fall rapidly. He suggested I eat something to get

my metabolism going, so I had some trail mix. In the following swells, it was a wet ride. While

Garys motor mount had been completely out of the way so far, it was now hitting the water

between swells. The water would hit the mount, then shoot straight up just before showering the

skipper. Back to the drawing board on that one, I guess.

We landed on Scorpion landing at 8:30pm, after approximately 11 straight hours on the water,

and 1 hour before high tide. As far as tide levels go, we could not have picked a worse day. The

tide level on this evening was the highest of the year. While the waves were breaking on a sandy

beach as we landed, the high tide line was at a line of boulders, which stretched the entire length

of the cove. The waves would be on the rocks in 1 hour. If we intended to spend the night, the

two of us would have to drag a 500 lb. catamaran over the rocks. Either that, or we would need to

leave this beach in the dark, to loiter in the dark harbor until the tide receded. To take no action

would have the boat smashing against the rocks in the next 60 minutes. I must admit, things

looked a bit grim at that point. We landed on Scorpion landing at 8:30pm, after approximately 11 straight hours on the water,

and 1 hour before high tide. As far as tide levels go, we could not have picked a worse day. The

tide level on this evening was the highest of the year. While the waves were breaking on a sandy

beach as we landed, the high tide line was at a line of boulders, which stretched the entire length

of the cove. The waves would be on the rocks in 1 hour. If we intended to spend the night, the

two of us would have to drag a 500 lb. catamaran over the rocks. Either that, or we would need to

leave this beach in the dark, to loiter in the dark harbor until the tide receded. To take no action

would have the boat smashing against the rocks in the next 60 minutes. I must admit, things

looked a bit grim at that point.

In the near darkness stood a lone figure using a cell phone. Scott Dunn, a kayaker, had come down from the campground to use his phone in the only area where he had coverage: Scorpion Anchorage. He came over and asked if we needed any help, and I explained our situation. "I'll be back with some help in 15 or 20 minutes", he said, and walked off.  As we held the boat and waited for help, a wave hit the sterns, caught the

rudders and slammed them sideways. I heard a loud snap, then heard Gary

yell: "That was the rudder casting! It's history!". The upper starboard

rudder casting had snapped in half at the tiller bar. So while I held the

boat, Gary went to the sterns to remove the one good rudder before it was

also damaged. I remain amazed at how Gary managed to remove a ring ding underwater, lift the

pin out, and remove the rudder, all in 2 foot surf, without losing any parts. As we held the boat and waited for help, a wave hit the sterns, caught the

rudders and slammed them sideways. I heard a loud snap, then heard Gary

yell: "That was the rudder casting! It's history!". The upper starboard

rudder casting had snapped in half at the tiller bar. So while I held the

boat, Gary went to the sterns to remove the one good rudder before it was

also damaged. I remain amazed at how Gary managed to remove a ring ding underwater, lift the

pin out, and remove the rudder, all in 2 foot surf, without losing any parts.

The tide was climbing, and I was having second thoughts about our help ever getting there in time. "Maybe the guy just decided to bail and go back to bed.", I said. Just then, I saw a parade of lights coming down the beach. Scott had returned with about 15 kayakers, all wearing "coal miner style" flashlights on their heads. He handed me and Gary a light, then Gary explained our situation and how we wanted to lift the boat and lay it on the rocks above the tideline. The boat was easily carried by the group, and two of the guys had some wood planks to lay the boat on. After we unloaded all of our gear, one of them returned with a small cart to carry our gear to the campground. What a helpful group of folks!!. The help continued as the kayakers escorted us to an open campsite. Seeing that we only had flashlights to work with, they brought over a gas camping latern to use for the night. (I honestly thought these guys were capable of serving up some steak dinners too!) My priority at that point was to get out of the wet gear. It was clear that if we were to take the spray pants and wet suits off while standing on the ground, they were going to get very dirty. So we both stood on the benches of each side of a picnic table, with the latern on the table top. So there we were, completely lit up, in the middle of a darkened campground, knowing there were campers all around us in the darkness. When we got down to the swim trunks, we paused. Then Gary said, "Aww what the hell... I don't care.", and off came the trunks. When you are cold and unconfortable, with not many options for privacy, your modesty goes out the window. After changing, Gary broke out the bottle of champagne, and I remembered leaving the plastic glasses a half mile away, back on the beach. So we each swigged from the bottle, while we cooked up our military Meal Ready to Eat (MRE) rations. These units use a chemical packet in which water is added to produce heat. As meals go, they were not that good. However, after 11 hours of sailing, they provided some warm satisfaction. During dinner, we discussed our predicament with the rudder. We could think of no way to sufficiently splint the damaged casting without risking a breakdown on the water, where things would be virtually impossible to deal with should the seas be even moderately rough. After much deliberation, it was decided that we would remove the damaged rudder assembly completely, then place the good rudder on the starboard side (which would be downwind on our crossing). The tiller stick extension would be removed, and steering wold be accomplished using the rudder crossbar. Since our crossing would be on a broad reach, some steering could be facilitated with sail trim. Considering the crippled condition of the boat, we also decided to leave early in the morning, while conditions were light. Unfortunately, this meant we had to abandon our hiking plans, and head back home right away.  We arose at 6am, quickly had some cold coffee drinks and fruit, then broke

camp. The night before, we had confirmed that the Kayakers would be on the

beach at 9am, so we wanted the boat ready to go by then. We arose at 6am, quickly had some cold coffee drinks and fruit, then broke

camp. The night before, we had confirmed that the Kayakers would be on the

beach at 9am, so we wanted the boat ready to go by then.

By 9am, the boat was ready to go, except for the sails which we would raise on the water. The outboard motor was in place, and our heavy gear bags were on the beach. With the help of our Kayaker friends, we lifted the boat into the water. We then threw the bags on board, fired up the motor, and headed out into the cove. I will always remember the site of departing the beach, and getting thumbs up from the group of kayakers, some of them waist deep in water after holding the boat. The help we received from these strangers was truly remarkable. After getting the bags secured, and sails hoisted, we stowed the motor, and were on our way.  The weather was perfect for our limp home. Smooth seas, and a 7-10 kt wind. The boat

performed fine with one rudder and the chuter deployed. I took the tiller and Gary helped control

steering and helm pressure with sail trim. The weather was perfect for our limp home. Smooth seas, and a 7-10 kt wind. The boat

performed fine with one rudder and the chuter deployed. I took the tiller and Gary helped control

steering and helm pressure with sail trim.

About three hours later, we approached Ventura in time to see the start of the Milt Ingram Race. Unfortunately, with only one rudder, we could not hang around the area. We doused the chuter at the harbor entrance, and sailed to the docks. It is likely that every channel crossing will hold new lessons. On this trip we learned the importance of tide information, and that a catamaran cannot be on the beach at Scorpion should the tide climb over 6ft. We learned about protecting rudders from the surf. Most importantly, we cannot casually invite others to make this trip. In the midst of some of the roughest conditions we had, Gary shouted, "Id never persuade ANYBODY to be out in this!"

The Author on the beach at Scorpion Anchorage (low tide) My sincere thanks go to Gary for the use of his boat, and the honor of crewing for him. This crossing has been, by far, the most memorable cat sailing experience I have ever had. At the same time, like Gary, I cannot feel comfortable persuading anyone to attempt it. Its that hairy. For those who feel qualified to try it, however, I hope this account provides some value in assessing the risks and logistics. For further information, feel free to email either Gary or me. |